A few thought personal thoughts as we celebrate the 10th anniversary of Invent To Learn – Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom

It’s hard to believe, but it has been ten years since Sylvia Martinez and I published Invent To Learn – Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, a book called the bible of the maker movement in schools. We are grateful to the enormous number of educators who have read the book, now in 9 languages, across the globe. Their kind words and support of the book has been inspiring.

In the delicate, idea averse world of educational technology. I’m often dismissed as a bomb thrower, yet nothing could be further from the truth. All of my work has been about building bridges – between people, communities of practice, and powerful ideas.

In many ways, Invent To Learn, was a summation of the first 30 years of my career working in schools around the world and a decade of Sylvia Martinez’s work on student leadership and empowerment at Generation YES. We recognized the power of newly available fabrication and computation technology, along with the informal learning adventures achieving popularity at Maker Faires around the world, and thought we could make a contribution by situating those emerging technologies and renewed interests in hands-on learning within the context of progressive education. In many ways, the meteoric, yet short-lived success of Maker Faire, was posited as an alternative to schooling. Our view was different.

We believed that the maker movement, exemplified by Maker Faire, offered support for the sorts of learner-centered, joyful, creative, and constructionist learning environments educators we constantly battled to nurture. If the media attention generated by the Silicon Valley influencers, power brokers, and corporate leaders behind Maker Faire could help sustain the educational practices we value and learn something about learning along the way, this was a win-win scenario.

That said, our summer institute, Constructing Modern Knowledge, predated the publication of Invent To Learn by five years, and now in its 14th year, has outlasted Maker Faire. Our work continues undeterred by the proclivities of the marketplace or politics. The enduring success of Invent To Learn is likely due to its breadth. There is a little something for everybody in Invent To Learn. The book offers tips, tricks, shopping advice, project ideas, and explanations of new technology all in a context of powerful ideas about teaching and learning. From my perspective, Invent To Learn is about project-based learning, school reform, and the profound lessons I learned from my mentors, including Seymour Papert, Cynthia Solomon, Dan Watt, Molly Watt, David Thornburg, Edith Ackermann, David Loader and countless geniuses like Herb Kohl, Deborah Meier, Loris Malaguzzi, John Dewey, Angelo Patri, Lillian Katz, Constance Kamii, Jean Piaget, Dennis Littky, and Ted Sizer.

While consumer grade 3D printing may have over-promised and under-delivered, its time will come. I saw Bluetooth demonstrated approximately thirty years before it became useful, reliable, and intuitive. That said, many educators and their students use 3D printers to great effect on a daily basis and the mathematical, engineering, design, and debugging ideas required by 3D printing are timeless. The ability to make what you need when and where you need it is inevitable.

Some behind the scenes reflections about Invent To Learn

We wrote the first edition of Invent To Learn with great alacrity. The second edition took far longer to complete. Three prominent men (and a woman) played pivotal roles in the publication of the book. Right before publication, we read marketing guru, Guy Kawasaki’s book about “self publishing.” The book was so logical and his reputation so strong that we did everything he advised, even though the book was largely finished. One piece of his advice was the importance of hiring a copy editor. Lucky for us, Make Magazine Editor-in-Chief and Boing Boing co-founder Mark Frauenfelder mentioned that his wife, Carla Sinclair, was a copy editor. Her knowledge of the maker movement was invaluable in polishing our masterpiece prior to publication.

The third gentleman, Dr. Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab, graciously agreed to write the blurb on the back of Invent To Learn. I can never repay him for the kindness he has shown me over many years. His generosity gave Invent To Learn the greatest stamp of approval imaginable. Speaking of books, if you have not read Being Digital by Nicholas Negroponte, you must. Although the book is twenty-eight years old, it still offers great insights for anyone interested in the future. The book’s predictions were flawless.

Upon the release of Invent To Learn, Sylvia and I decamped for a long well-deserved vacation in the idyllic beach resort of Palm Cove, Australia, where the weather was awful nearly every day and we were consumed by interview requests, experts, and other publicity related activities related to our new book. 😎

We initially intended to produce a few books and then find a publisher, but reader interest and the emergence of print-on-demand technology made it possible for us to start Constructing Modern Knowledge Press. Not long after, we began giving voice to other educators with terrific ideas and have since proudly published approximately 15 other books, with more in development. During the pandemic, I launched Cymbal Press, to publish award-winning books by jazz musicians about their art.

The future

While some critics were quick to dismiss the maker movement as a call for bringing back bedazzled shop classes, it is worth noting that the secret sauce of the maker movement, computing, remains underrepresented in classroom making.

While cardboard captured the imaginations of teachers, far too few students are experiencing rich computing experiences in which they make things with code. Programming experience is essential in order to develop the computational fluency required for maintaining agency over an increasingly complex and technologically sophisticated world.

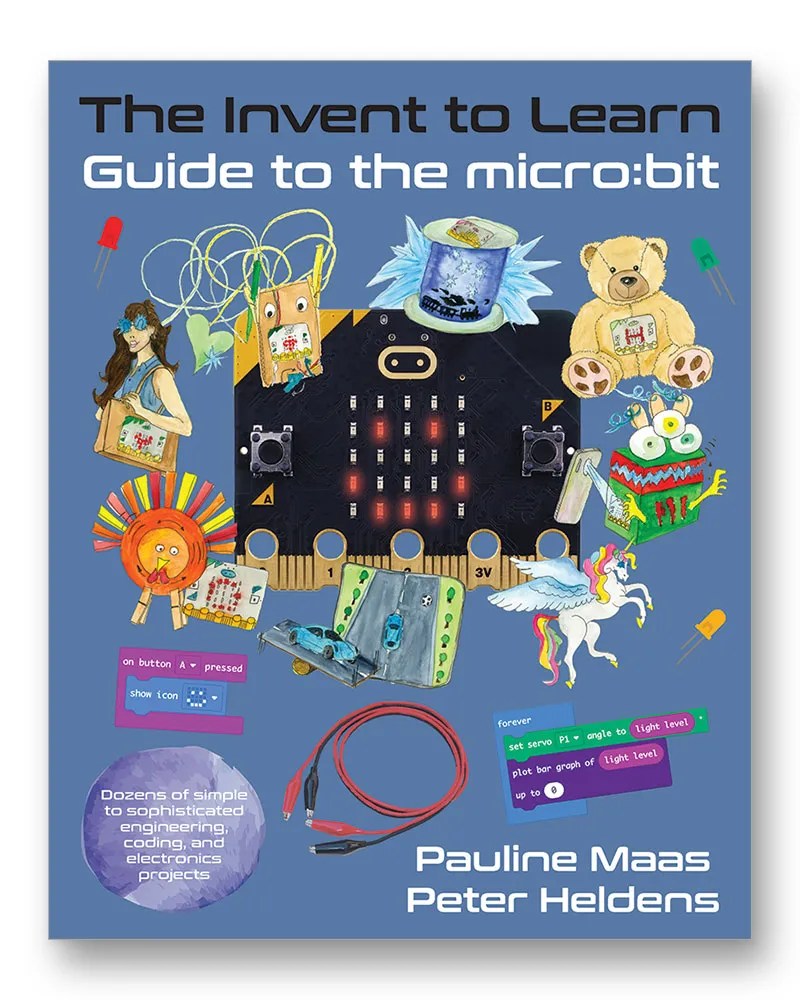

My recent online workshop, Coding in the Age of AI (now available freely on-demand) is one attempt to encourage more classroom computing. Our recent CMK Press books, The Invent to Learn Guide to the micro:bit and Twenty Things to Do with a Computer Forward 50: Future Visions of Education Inspired by Seymour Papert and Cynthia Solomon’s Seminal Work, help educators bring rich computational experiences to children.

My final essay in Twenty Things to Do with a Computer Forward 50 is titled, The Future is Computational. I recommend reading it along with the work of 45 colleagues from around the world to anyone interested in realizing a creative, complex, and fulfilling life in an undoubtedly uncertain future.